MORE THAN ONE and half millennia ago, a wandering monk stopped at an oasis.

The area in western China, some distance outside the town of Dunhuang, was known for its stunningly beautiful crescent-shaped spring, and its “singing” sand dunes: the winds there sometimes made a rhythmic musical sound.

The monk, named Lè Zūn (樂尊, which can also be pronounced “Yue Zun”) noticed some cave openings in the cliffs above a river. He felt that there was something special about the location and decided to stay and make it his home. He started digging out the cave to live in about AD 366.

Another monk, Faliang, joined him, and then another, and another.

Over the centuries, thousands of pilgrims arrived and decided to stay in what had become a holy place, digging out more caves, and spending their time praying, chanting, and—most importantly—creating sacred art on the walls. They also made sculptures and collected ancient books.

The Dunhuang area, in the Gansu-Xinjiang desert region, became a key crossroads on the new Silk Road, a trade route taking goods between Xian and Central Asia – and visitors were thrilled to stop for a break, and take candles into the caves to experience the art on the walls.

It was a huge success for many hundreds of years.

LOST TO HISTORY

But time passed and habits changed. More than 1,000 years after the caves’ first resident had arrived, travellers starting taking other routes, as shipping lines improved, and the Silk Road gradually became quiet.

The remaining monks in the caves eventually died off and there was no one to take their place.

The Mogao Caves in the Dunhuang district of Gansu province in west central China were completely forgotten, and for hundreds of years, they were nothing more than a dusty legend, holes in the cliff wall, known only to the local people.

ANOTHER WANDERER

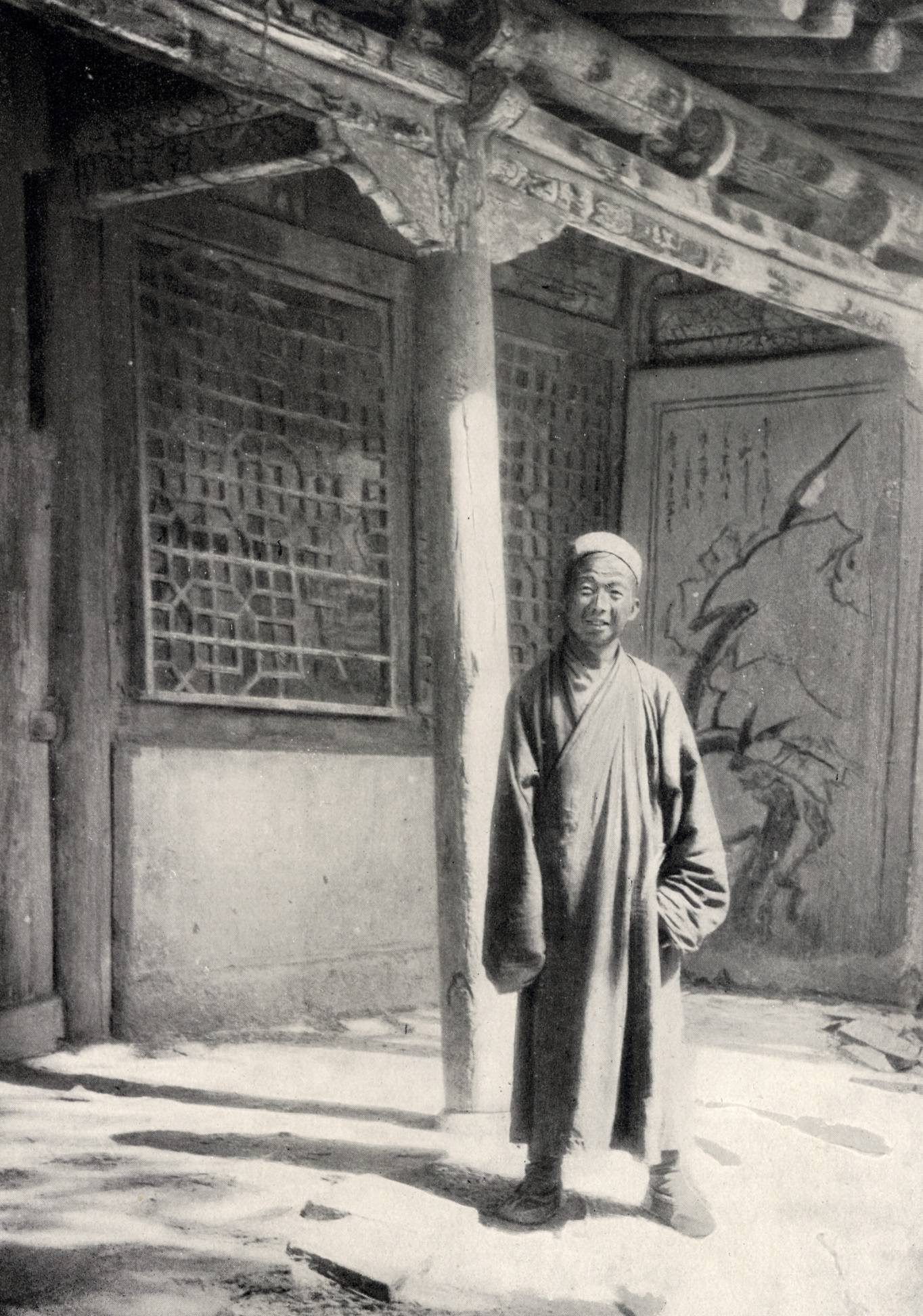

Then, in the late 1800s, another travelling monk, Wang Yuanlu, came upon the site. He felt the pull of ancient magic and decided to stay there and dig into the caves. He was stunned at what he found.

News of the amazing treasures of art and ancient scrolls eventually went out to the world, and over the following decades, international scholar-explorers took an interest.

The caves released some breathtaking secrets. There were hundreds of caverns containing some of the world’s finest ancient paintings, sculpture, and literature.

The complex of caverns were like a tunnel to a lost world. For example, explorers found the Library Cave, a room full of books that had been untouched since the year AD 1002.

Inside, they found the oldest book in the world: the Diamond Sutra. It had been written in AD 868. While there are older written works in existence, they are fragmentary and undated. The Sutra is the oldest complete, dated, printed book.

After finishing his daily walk, the Buddha sat down to rest, and an elder named Subhuti came to him with questions. . . The great one told him that all phenomena were ultimately illusory.

The Diamond Sutra, 868 AD

Today, the Mogao Grottoes on the outskirts of Dunhuang city are the world’s largest and most valuable treasure trove of Buddhist art.

Every year, hundreds of thousands of people visit the Thousand Buddha Grottoes, carved into rock cliffs above the Dachuan River.

More than 730 caves had been carved over a period of 1,000 years from the fourth century onwards. Almost 500 caves have exquisite hand-made frescoes, covering about 45,000 square meters of walls with spectacular murals, and the grottoes also house more than 2,000 beautifully-coloured sculptures.

These artworks are not just beautiful, but capture numerous aspects of politics, culture, arts and religion in ancient China.

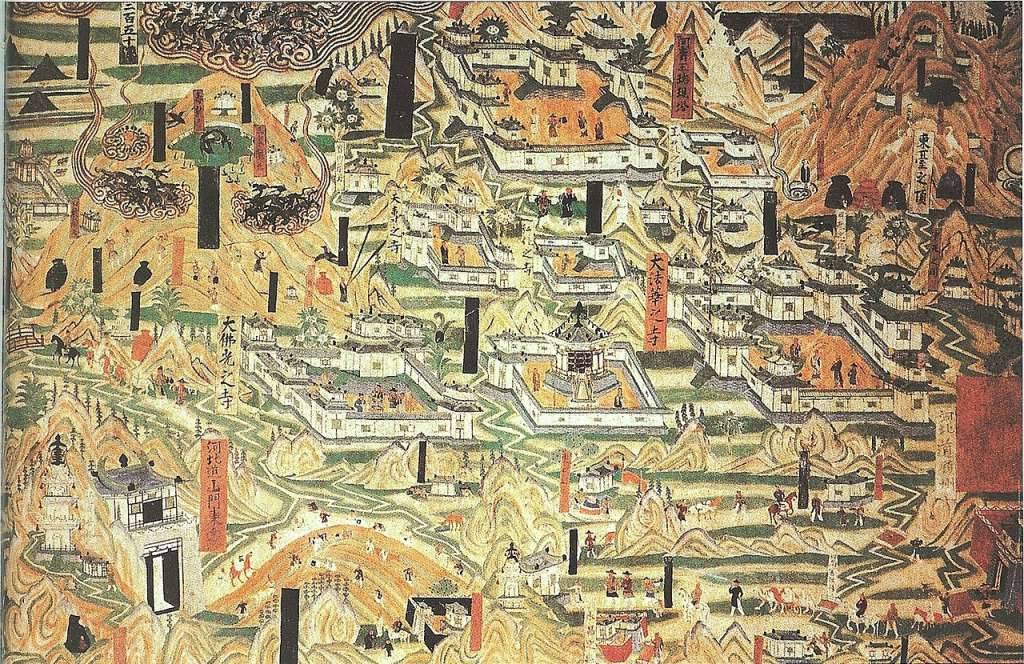

One of the finest paintings is in Cave 61, and depicts Wutai Mountain, one of the renowned Buddhist sacred peaks in China’s Shanxi province. The colourful painting shows many buildings and hills and is considered an exemplary example of an early topographic map.

Another favorite spot for visitors is the Nirvaṇa cave, number 158, which gives visitors an astounding view of a reclining Buddha. Paintings of paradise decorate the walls of the cave-temple.

Yet today, the Mogao caves are threatened by climate change and the effects of tourism. The caves’ delicate murals face damage caused by hundreds of thousands of tourists’ visits per year, whose presence has filled the delicate cave air with carbon dioxide and humidity.

The development of new technologies for preserving and documenting the grottoes has become critical to their long-term survival. The Dunhuang Academy, which preserves and restores the historic site, is working on a digital archiving project, photographing the caves and a myriad of mural paintings and sculptures.

Professor Fan Jinshi, director of the Dunhuang Academy, has taken the lead in protecting the invaluable cultural relics and ensuring the caves are meticulously documented and the art shared around the world. Several Hong Kong scholars are also playing a part.

The exquisite art and relics reflect changes in religious beliefs and rituals over the centuries and have become a veritable treasure house of Chinese history.

The original monk, Lè Zūn, was certainly right when he felt, one and half millennia ago, that there was something special about the place.

Click here for more stories about Chinese history and culture.